Art

Advertising

- Advertising

- Tin (Cassiterite) Distribution: Mediterranean Bronze Age

- Archaeological Sites of the Aegean Minoans

- Extent of Santorini Eruption's Tsunami Inundation of Minoan Crete

- End of Minoan Linear A Writing and LM IB Fire Destruction of Crete

-

Nature Geoscience Journal and

Late Minoan IB Destruction Event -

The Cause of the End of the Bronze Age

with the Scientific Method - Prehistoric Star Navigation, Eastern Mediterranean Ethnocentric Bias, and the "Cabal of Certainty"

- Theoretical Bronze Age Minoan Heliographic Aegean Network Validated by 92.15 Mile (148.3 Km) Mirror Sunlight Flashes

- The Validation of a Bronze Age Minoan Heliographic Aegean Network in Southern California

- Tsunami Generation from the Titanic Bronze Age Minoan Eruption of the Santorini Marine Volcano

- The Cento Camerelle Mines of Tuscany: A Major Bronze Age Source of Tin

- No Men or Sails Required: Successful Prehistoric Sea Travel

- Minoan Downfall and Volcanology's Black Hole of Unknowns

- Homer and Navigating by the Stars in Prehistory

- Primacy of Human Powered Rowing in Copper Age and Minoan Shipping

- Minoan Invention of the True Dome and Arch Prehistoric Mediterranean Catenary Architecture

- "Sinking Atlantis" Tsunami Myth Debunked

- Minoan Tholos Structural Mechanics and the Garlo Well Temple

- Minoan Web of Mirrors and Scripts

- Santorini Eruption and LM IB Destruction

- Minoan Catastrophe: Pyroclastic Surge Theory

- Early Minoan Colonization of Spain

- Origin of the Sea Peoples

- Minoan Ship Construction

- Minoan Maritime Navigation

- Ringed Islands of Thera, Santorini, Greece

- Minoan Scientific Tradition

GIS Google Earth

Publications

Publications

Official Art Gallery

A Collection of 20 Paintings each with over 70 Art Products

There were many Minoan ship masters that travelled the open sea routinely on busy, especially in summer, well-established trade routes throughout the entire Mediterranean Basin and into the Atlantic. They used every available indicator in nature and compared it to a mental navigational map stored in their mind to plot a course. They focused on the sun, moon, stars, the predictable seasonal winds, and other indicators to guide them.

Navigating by the Sun

The Sun at Noon in a Haze

On a clear day when the sun's position can be observed, the sun arcs in the sky relative to the horizon from the northeast at dawn to rise to its midday zenith and then arcs down toward the northwest to set in the evening. The position of the sun at it's noonday zenith indicates north by sighting a line from the horizon through the center of the sun. The north-south position of the sun's arc across the sky changes with the seasons. With this in mind, they could dependably deduce directional information from its position in the sky at any time during the day.

Using the Moon to find North

The light we see from the moon is the light it reflects from the sun. Whenever a crescent shape, either light or dark, can be seen on the moon's surface it gives an observer the ability to determine a northerly direction. By sighting a line that connects the endpoints of the crescent it indicates a northern heading. Also, if the moon rises before sundown, the illuminated side indicates the west. If the moon rises after midnight, the illuminated side indicates the east. This provides a navigator with a rough east-west reference in the night sky.

Using the Moon's Crescent to find North

The Moon's Libration

The Celestial Navigation of the Ancient Minoan Mariners

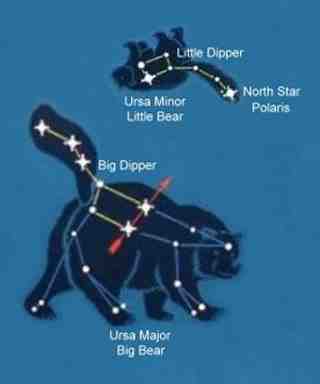

On a clear night, the countless stars gave the mariners many more points of reference to help them navigate more precisely. There were stars in all quadrants of the night sky moving in a predictable, orderly way from dusk to dawn and season to season throughout the year. They used two groups of stars that were always visible above the horizon and rotated about the North Pole. They called them the "Two Bears". In our time they are known as Ursa Major (Great Bear, Big Dipper, Plough) and Ursa Minor (Little Bear, Little Dipper).

The star used to sight the North Pole has changed over the millennia due to the precession of the Earth's rotational axis. While today Polaris (430 light-years away) is quite close to the North Pole, in the past other stars more closely indicated true north. Thuban, a star in the constellation Draco, was the North Star before about 1900 BC when the much brighter Kochab (Beta Ursae Minoris) took its place. Kochab is the second brightest star in the cup of the Little Dipper. No matter what star was used in any given era to indicate true north the bright stars of the "Two Bears" could always be used to sight it. The Bears rotate about the North Pole and change their orientation to it as the seasons change. The ancient navigators could tell what season it was simply by looking at the orientation of the Bears relative to the North Pole in the evening sky.

The star used to sight the North Pole has changed over the millennia due to the precession of the Earth's rotational axis. While today Polaris (430 light-years away) is quite close to the North Pole, in the past other stars more closely indicated true north. Thuban, a star in the constellation Draco, was the North Star before about 1900 BC when the much brighter Kochab (Beta Ursae Minoris) took its place. Kochab is the second brightest star in the cup of the Little Dipper. No matter what star was used in any given era to indicate true north the bright stars of the "Two Bears" could always be used to sight it. The Bears rotate about the North Pole and change their orientation to it as the seasons change. The ancient navigators could tell what season it was simply by looking at the orientation of the Bears relative to the North Pole in the evening sky.

The Movement of North Star and Stars in Night Sky

The Two Bears and the North Star

The Big Dipper and the Seasons

Polaris also gave them their north-south position (latitude) by observing the angle it made with the horizon. The North Star is significantly higher in the night sky in the far northern Aegean and lower in the sky if they were well south near the coast of Egypt on any given night.

The North Star and Latitude

They probably used a simple tool to more precisely measure the angle of the North Star relative to the horizon. It was composed of two cleanly sawn, thin sticks of wood that were about a half meter long. The two sticks were joined together on one of their ends into a hinge that pivoted on a small peg. The free end of the top stick pointed to the North Star, and the bottom stick pointed to the horizon. A string with a lead bobbin hung from the top stick. By opening and closing the sticks, the length of the string from the top one to the bottom one could be measured. They could get a good measure of the angle of the North Star from their position with this simple instrument. With a good initial angle measurement (fix) as a reference, if they knew what the difference of the angles was between the angle of their starting point and the angle of their destination they could deduce their destination's north-south position at any time of the year; no matter where they were in the open sea.

Other Navigational Indicators and Tools

To this they added the information gathered from the direction of the seasonal winds. If the wind died down, they would look at the swells on the sea. The direction of the wind could be estimated from the swells long after the wind had ceased. If the winds died completely or were confused, they would look for birds, like the terns, that fed at sea during the day and flew back to land with the approaching sunset to indicate a nearby landfall.

Minoan Miniature Frieze Admirals Flotilla Restoration Fresco

Shipping Scene

Late Bronze Age (LBA)

Neo-Palatial Late Minoan I Period

West House, Room 5, South Wall

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

Shipping Scene

Late Bronze Age (LBA)

Neo-Palatial Late Minoan I Period

West House, Room 5, South Wall

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

Knowledge of the predictable seasonal winds aided them greatly in navigation. For example, the predominant winds in the Aegean Sea are the north and northwest winds. The north winds of winter and the northwest winds of summer can sometimes grow into strong gales that can easily blow a ship out of control downwind. The other important winds are the East wind that blows in summer and fall, the West wind of late spring and early summer, the stormy South winds of late summer and autumn, and the Southwest wind of spring and late fall. They categorized each of the winds with its own set of attributes such as dry, wet, hot, cold, dusty, clear, strong, weak, etc.

They took a measure of the ship's speed in the water using a large piece of cork with a light line of rope attached to it. A mariner at the stern of the ship would drop the floating cork into the sea and count the number of heartbeats it took before the line tightened in his hand. Another instrument they found useful in coastal areas, especially in the perilous shallows near the mouth of the Nile, was the sounding lead. It was a weight of lead tied to a rope used to determine the depth of the water when thrown overboard. It could also be used to detect the composition of the seabed and give them an indication of how much anchoring would be required to hold the ship in position in the current.

The sun, moon, stars, winds, and their instruments provided the ancient Minoan mariners with reliable information they could compare with their navigational mental map to dependably get a reasonable fix on their position and determine their ship's heading in the open sea far beyond the sight of land.

They took a measure of the ship's speed in the water using a large piece of cork with a light line of rope attached to it. A mariner at the stern of the ship would drop the floating cork into the sea and count the number of heartbeats it took before the line tightened in his hand. Another instrument they found useful in coastal areas, especially in the perilous shallows near the mouth of the Nile, was the sounding lead. It was a weight of lead tied to a rope used to determine the depth of the water when thrown overboard. It could also be used to detect the composition of the seabed and give them an indication of how much anchoring would be required to hold the ship in position in the current.

The sun, moon, stars, winds, and their instruments provided the ancient Minoan mariners with reliable information they could compare with their navigational mental map to dependably get a reasonable fix on their position and determine their ship's heading in the open sea far beyond the sight of land.

2007

W. Sheppard Baird

Copyright © 2007, 2024 W. Sheppard Baird

All Rights Reserved

All Rights Reserved

-

Mediterranean Sea

-

Minoan Miniature Frieze

Admirals Flotilla Fresco

Shipping Scene Restoration

West House, Room 5, South Wall

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Minoan Dolphins Restoration Fresco

Knossos, Crete, Greece

-

Minoan Ship with Rowers Only

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Minoan Ship with Sail Only

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Minoan Octopus Fresco

Knossos, Crete, Greece

-

Aegean Sea

-

Aegean Vase with Ship Figures

1700BC

-

Arsenical Copper Bulls

Standard with Two Long-Horned Bulls

2400 - 2000 BC

Early Bronze Age III

North Central Anatolia

-

Egyptian Bronze Saw

Egypt, 1350 BC

-

Minoan Flying Fish Fresco

Phylakopi, Milos, Greece

-

Minoan Miniature Frieze

Admirals Flotilla Fresco

Thera Scene

West House, Room 5, South Wall

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Spring Fresco West Wall

Swallows Scene

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Minoan Ladies in Blue Fresco

Knossos, Crete, Greece

-

Minoan Bull Leaping Toreador Restoration Fresco

Knossos, Crete, Greece

-

Minoan Sea Daffodils Lilies Restoration Fresco

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Minoan Boxing Boys Restoration Fresco

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Minoan Antelope Restoration Fresco

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Minoan Boxing Boys Fresco

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece

-

Minoan Priest King

Feathered Prince of Lilies Fresco

Knossos, Crete, Greece

-

Minoan Sea Daffodils Lilies Fresco

Akrotiri, Santorini (Thera), Greece